A record number of Black women are running for Congress this year. At least 122…

From Emancipation to Voting Rights: The Tradition of Black Women Organizing

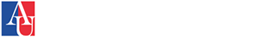

On January 5th the Georgia Senate Runoff election was the culmination of a sprint by Democratic organizing groups to flip two Republican-held Seats in a state that hadn’t had Democratic Senators in a generation. The groundwork for the Senate flip was laid almost a decade ago by Black and other women of color leaders, most recognizably former Georgia House Minority Leader and former 2018 Candidate for Governor of Georgia Stacey Abrams. And the long-term organizing for voter access descends from a proud tradition specifically in the South to push America to live up to its own democratic ideals.

The story about Stacey Abrams is well known at this point. In 2011, when she became Minority Leader, she determined from looking at the demographics change in Georgia that the best way to build Democratic political power was to register and organize more people to vote. She started the New Georgia Project as a vehicle to register more voters in 2014 and then hired Nse Ufot to continue managing the Project as Abrams served in the State Legislature. Since its founding 500,000 plus voters have been registered by New Georgia Project, and other organizations led mostly by Black and other women of color leaders also put down stakes in Georgia to engage other voters who had long been ignored in the political process: Black Voters Matter, Asian Americans Advancing Justice, and MiJente.

Pre and post-emancipation, Black women organized, advocated, wrote and spoke for their own legal liberation and eventual suffrage. Those 19th-century women were well-known heroes like Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman and lesser well known but no less powerful: Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, Mary Ann Shadd Cary and Maria Stewart. They traveled around the US, educated, lobbied, and organized for the vote for themselves. The legacy was then picked up by the next generations of Black women leaders in the early 20th century like Ida B. Wells, a journalist who crusaded against lynching in the Jim Crow South and organized for suffrage along with Mary Church Terrell, a major player in building up Black women’s clubs into advocates for the Black community. When the fight for suffrage in the 1920s ended in only white women securing the vote, Black women continued in their advocacy and organization for another couple of generations.

The fight for democracy through the 1950s and 1960s was most famously seen in the faces of: Diane Nash, co-founder of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee and a voting rights organizer who was a major participant in the march in Selma with her colleague and future Congressman John Lewis. There was Septima Clark, called the “Mother of the Movement” who jeopardized her own livelihood as a teacher to conduct citizenship workshops for Black people in the Jim Crow South. The workshops taught people basic literacy skills (to evade poll tax literacy tests), their rights and duties as U.S. citizens, and how to fill out voter registration forms. And then there was Fannie Lou Hamer, who not only helped register Blacks to vote in Mississippi but was also a key organizer of the well known “Freedom Summer” project in Mississippi. She was also the face of the fight for Black enfranchisement at the 1964 Democratic National Convention, when she demanded her multi-racial delegation be seated instead of the all-white delegation of Mississippi. And there are countless more Black women who go nameless in the Civil Rights movement and who gave their time–and sometimes their lives–for democracy.

And that tradition has continued into the 21st century. In the face of voter suppression that targets communities of color, Black women and other women of color, descendants of the organizing tradition Black women before them forged, organized their communities in 2020 in Wisconsin, Michigan, Texas and across the country and, yes, several times in Georgia to win victories considered essential for the change they sought.