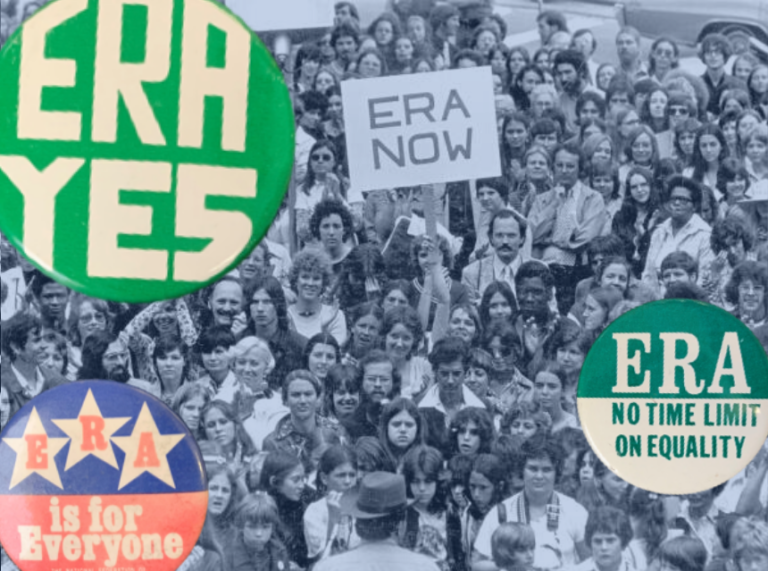

What is the ERA? The text of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) is short…

The Struggle Over the Equal Rights Amendment Is Not a Typical Political Fight

The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) is in the news lately because three more states have ratified the amendment in recent years: Nevada (2017); Illinois (2018); and Virginia (2020). These state ratifications have presumably given the amendment the necessary thirty-eight state approvals needed for ratification. But questions over the continued viability of the congressional deadline on the amendment (originally set as 1979 but extended in 1978 to 1982) have prevented the ERA from being fully incorporated into the Constitution.

For several amendment supporters, Congress holds the key to clarifying the lingering legal issues surrounding the ERA. According to this view, Congress could remove the amendment’s deadline and, thereby, clear the path for the President to direct the U.S. Archivist to certify the amendment. The fate of this strategy hinges on the upcoming mid-term elections, since the election of more pro or anti-ERA congressional members could determine if Congress will sidestep the amendment or move it past the finish line. In either case, it is vital for ERA advocates and critics to remember that the amendment has a long history of attracting and repelling Democrats and Republicans alike.

Because of the ERA’s turbulent history during the state ratification battles of the 1970s, the amendment is often presented today as a natural wedge issue between Republicans and Democrats. When Congress sent the ERA to the states for ratification in March 1972 more Democrats had come to support the amendment due to a greater recognition within society of the diversity of women’s capabilities. In turn, by the mid-1970s, the revitalization of grassroots conservatism spearheaded by right-wing author Phyllis Schlafly had pushed more Republicans to oppose the amendment as a threat to the stability of the American family.

Yet, as I explain in Gendered Citizenship, the ERA has a deep history of transcending conventional political divides. Before the 1970s, conservative and liberals were drawn to both the pro and anti-ERA positions. When the pro-ERA position gained momentum in the late 1930s and 1940s, for example, support grew to include pronounced liberal and conservative variations. In the minds of liberal ERA proponents, such as President Franklin Roosevelt’s second Vice President, Henry Wallace, passage of the ERA would allow government officials to expand economic regulations to protect men and women workers equally. The ERA also had the backing of conservatives like Republican politician George Wharton Pepper. For conservative ERA backers, passage of the amendment would secure the right of all citizens to freely compete in the economy. While conservative and liberal ERA proponents differed in what they believed they could achieve with the amendment’s passage, both groups supported the ERA to ensure that a single standard of rights applied to all citizens regardless of sex.

Likewise, the opposition to the ERA has a bipartisan history prior to the 1970s. Liberal ERA opponents included the first woman Secretary of Labor, Frances Perkins, while conservative amendment opponents included Republican Senator Robert Taft of Ohio. Both liberal and conservative ERA critics believed that women had a natural right to special protection; they just differed over who should provide women with that protection. For conservative ERA opponents, women’s special protection should come from the male head of the household, while liberal ERA opponents claimed that government reform efforts could also provide women with protection.

At its core, the ERA struggle is not a typical political fight; it is a deep ideological conflict over the rights of U.S. citizens. Before the later state ratification battles, ERA proponents and opponents were able to create coalitions for their positions that not only lasted for decades but also surpassed traditional political divides. The ERA’s long dynamic history reminds us that it is possible for both sides to create those coalitions once more.