As we welcome Saturday Night Live back to the airwaves, we’re reminded that, over…

Why Didn’t Women Win it for Hillary?

In 2016, the U.S. had a notable first: a female presidential nominee of one of the major parties. Yet, compared to prior Democratic nominees, women did not overwhelmingly vote for Clinton, refuting a simplistic narrative about how gender should influence politics.

The conventional wisdom is that women are more likely to vote for women and men for men. In reality, what matters most are voters’ and candidates’ attitudes about gender. Is feminism important to the voter, or are they a gender traditionalist? Is the candidate hostile toward women, or are they egalitarian? We find that whether a voter shares a candidate’s views on gender (what we might call an “attitude match”) is much more important than whether the voter shares a candidate’s gender (a “gender match”).

To demonstrate this phenomenon with an example, consider that, in 2008, female as well as male Republicans enthusiastically supported Vice Presidential candidate Sarah Palin. Part of Palin’s appeal to conservatives of both genders was her opposition to feminism and support for traditional women’s roles.

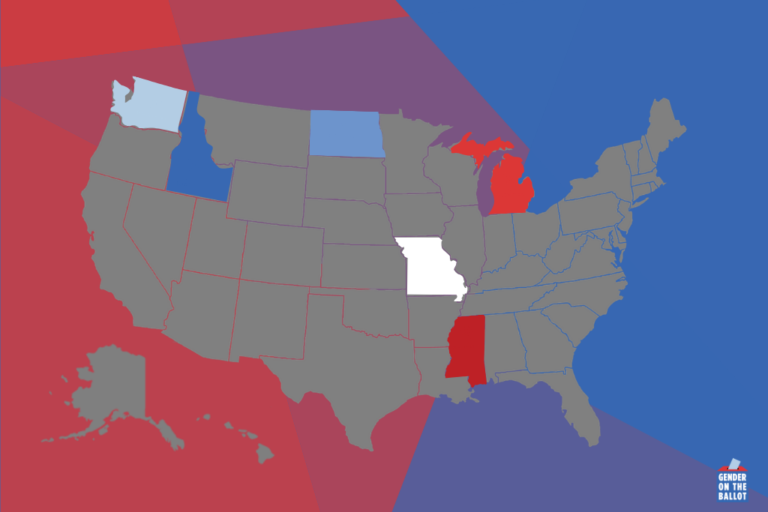

To investigate the relationship between gender attitudes and vote preferences, we fielded a survey during the 2016 primaries. We asked a representative sample of American adults to evaluate the leading Democratic (Clinton and Sanders) and Republican (Trump, Cruz, and Kasich) candidates. We also posed questions that measured three types of gender attitudes—gender traditionalism, beliefs about whether sexism remains a problem in society, and hostility toward women. In a series of statistical analyses—which controlled for respondents’ partisanship, gender, and other demographic characteristics—we then examined the direction and strength of the association between voters’ gender attitudes and their candidate preferences.

Our study reveals the crucial importance of gender attitudes. Focusing on the general election contest, all three types of gender egalitarians strongly preferred Clinton to Trump. And this attitudinal similarity mattered more to voters’ preferences than whether they themselves were male or female. We also demonstrate that an attitude match is more important than a gender match. If Sanders had won the nomination, our study indicates that feminists and women would have supported him (vs. Trump) at nearly the same rate as they did Clinton, leading to the same outcome in the general election (at least in regards to the influence of gender).

The importance of gender attitudes can be observed in primary contests too, although they are more subtle because candidates vying for a party’s nomination tend to hold similar views on gender. As we expected, among Republicans, gender egalitarians preferred Kasich to Trump. Among Democrats, findings were complicated—gender traditionalists actually preferred Clinton but hostile sexists preferred Sanders. In short, “Bernie Bros” were real, but settling on this narrow read of gender and elections misses the bigger picture.

From: “Gender Attitudes and Candidate Preferences in the 2016 U.S. Presidential Primary and General Elections.” Politics & Gender. Link: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/politics-and-gender/article/abs/gender-attitudes-and-candidate-preferences-in-the-2016-us-presidential-primary-and-general-elections/9D9989B71E0832DFC10310337D27F1BF